“When we started talking about migration [as a conference theme], everybody said ‘don’t do it, it’s too controversial.’ We said that’s exactly why we’re going to do it.”

This is how Martin Barry, Chairman of reSITE, opened their 2016 Conference in Prague, titled “Cities in Migration”. The anthropocene city is in a constant flow of migrations. It has ambitious development goals that cater to the non-human exchanges but fails to take responsibility for the human exchanges. It sweeps its plans under the carpet of ‘sustainable society’ but is in fact, moving further away from the same. To this end, the key question that was discussed at the conference, which also needs to be evaluated by cities today, is how diversity can be acknowledged, respected and accommodated by the built environment. By situating this question in the context of Stockholm, it can be seen how social sustainability is challenged by an uncountable number of historical, political and economic issues related to migration and how residents in certain neighbourhoods are subject to disadvantages caused by spatial manipulation (Sayer & Storper, 1997).

Over the past decade, the City of Stockholm has seen an increase of more than 15,000 inhabitants a year. By 2050, Stockholm County is expected to host 3.4 million inhabitants. This population growth is due to a high birth rate and a high degree of migration. However, the existing and newer citizens are not integrating into the city in all the ways they should. The region as a whole has also become increasingly polarised in living conditions, health and education. The Stockholm City Plan for 2040 acknowledges the increasing segregation among citizens from different backgrounds and different socioeconomic circumstances but does not explicitly present policies to overcome these social injustices occurring at the municipal level. As Susan Fainstein (2014, p.5) comments, “Although there is a rich literature in planning and public policy prescribing appropriate decision-making processes, these process-oriented discussions rarely make explicit what policies would produce greater justice within the urban context. At the same time, most policy analysis concerns itself with best practices or what works in relation to specific goals like producing more housing or jobs without interrogating the broader objectives of these policies.”

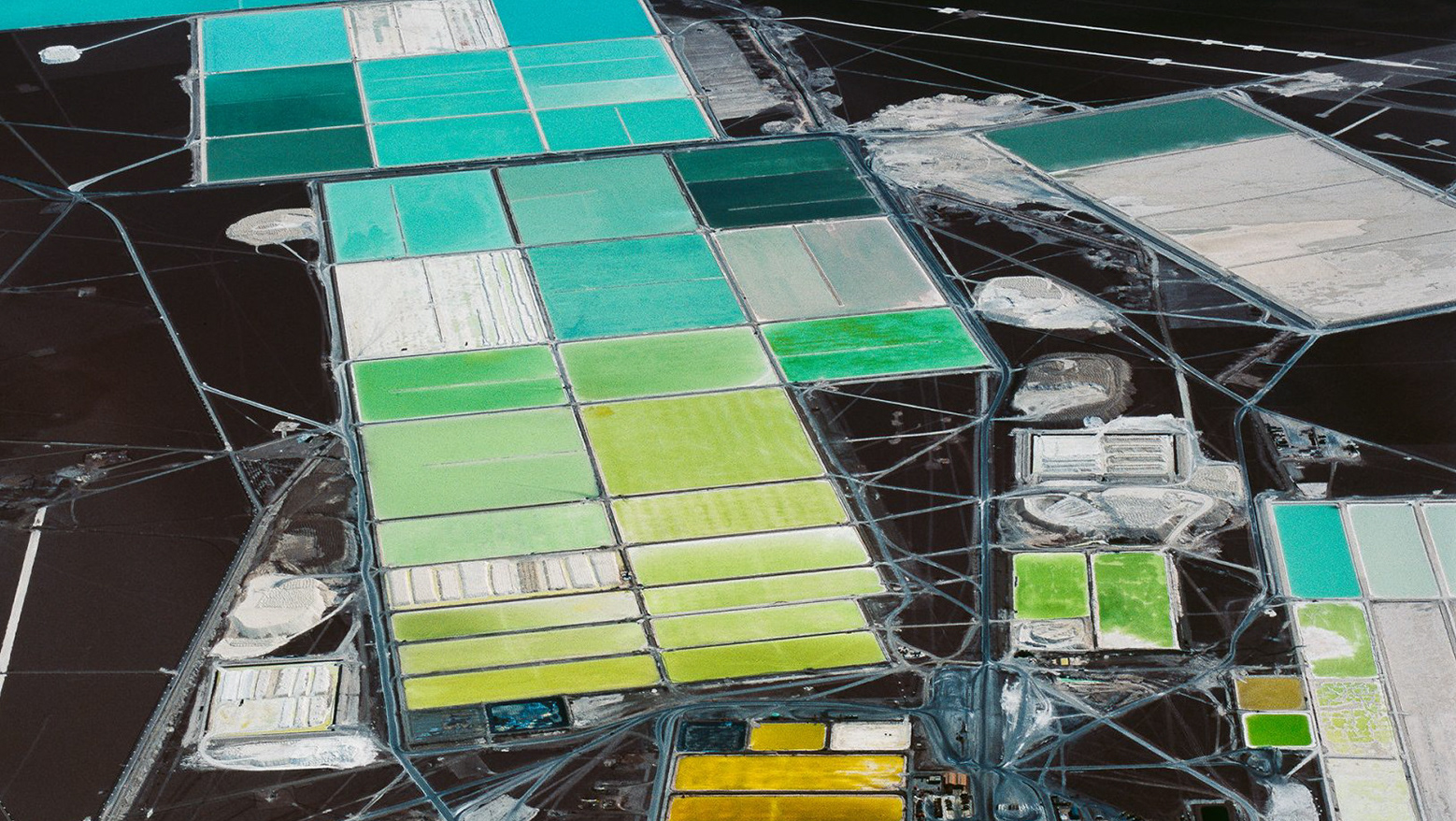

Figure 1: An approximated hotspot map of Stockholm Region based on Trygghets Kommissionen’s Security Survey 2020, overlayed with the forces challenging social sustainability, as discussed in the essay.

One of the long-term challenges identified in the Regional Utvecklingsplan För Stockholm 2050, is for the city to become an internationally leading metropolitan region in a growing global competitive landscape and also Europe’s most attractive metropolitan region. This planning approach seems to be borderline obsessed with the idea of metropolitanisation. Schierup et al (2014, p.10) sees the Swedish riots of 2009 & 2013 as a result of set-backs in decades of Swedish urban policy, including the national large-scale ‘Metropolitan Policy’ adopted by parliament in 1998. From the perspective of social injustices, these policies harbour significant flaws, including the omission of a focus on racism and discrimination, linked to the wider political economy and structure of power in cities. “Plans for urban restructuring and moves to combat growing urban segregation and social inequality have largely been quashed by the major policy trends of the 2000s – from ‘welfare’ to ‘workfare’ and from public sector and civil society partnerships to market-driven projects.”

It is essential to relate Swedish urban development to the historical contexts and the origins of segregation (Schierup et al, 2014). By doing so, one can draw similarities which shouldn’t exist, given the range of societal changes that have occurred between then and now. As reported in Stockholm Architecture and Townscape (Andersson & Bedoire, 1988), when the construction of tramways began in the 1870’s, a process to burst from the bounds of the city began simultaneously. This created a differentiation in the urban fabric which set off the unmanageable urban sprawl. Central functions were occurring around the inner city while factories and workers housing formed segregated enclaves away from the well-to-do districts. As the suburbs acquired tram services, urban sprawl materialised. These areas were stamped and cut straight through by the city’s roads and rail communications with the outside world. In addition there was the road network between the suburbs, along which unplanned variegated settlements grew. The city planners were unable to predict these settlements in the fringe areas or find room for them elsewhere and thus considered them a “troublesome heritage”. The perception of unplanned settlements being “troublesome” has continued to stay on and is now widespread among ordinary citizens. While present day planners are frustrated from the challenges they face to plan for social justice, it is ironic that planners themselves established this term a few generations ago.

Another urban development similarity can be seen in the overarching structure of the city. The mediaeval urban fabric of Stockholm was concentrated around a central square including a town hall and a civic church. In 1928, the renewal of the inner city became a priority and a comprehensive growth approach was adopted in the first masterplan (Andersson & Bedoire, 1988). Even today the 2040 plan emphasises, on multiple accounts, the power of an attractive inner city and creating dense neighbourhoods around it. A survey of the office market in Stockholm shows the tendency of offices to open in central locations, which is currently only concentrated in the inner city, Kista, Solna and Sundbyberg districts. Knowingly or unknowingly, the master plans for the future are following the past practices which create unequal distribution of urban assets, thus increasing socio-economic segregation.

Since the Second World War, many heavily industrialised countries underwent economic restructuring and urban transformation. In France and Sweden, this restructuring was confined mainly to working class neighbourhoods in the peripheral areas of cities that became the equivalents of US and UK inner cities, suffering from economic problems, stereotyping and stigmatisation (Dikeç, 2016). The Swedish förorten (suburbia), like the French banlieue, signifies deprived municipal housing areas inhabited by a majority of poor immigrants and other disadvantaged groups. Like Young and Harvey, Soja (2010) has highlighted the concept of uneven development, where geography is a significant causal force in explaining [inequitable] social relations and societal development. “It’s incredibly important to keep the cores of the cities as diverse as possible,” explains Mimi Hoang, principle of nArchitects with the example of the French banlieue revolts. “This obviously creates feelings of ostracization and marginalization….the reality is that if the working class is in the periphery of the city, that is creating a hotbed of resentment.” These feelings become the starting point for urban rage, which builds up from exclusions—from good jobs (or simply jobs), desirable social positions, decent housing, good schools, pleasant neighbourhoods (Dikeç, 2016). The Stockholm riots are a key example of urban rage which grabbed international attention on the geography of urban inequality (Schierup et al, 2014).

Fittja, a satellite city of Stockholm, was constructed as part of the Million Programme initiated by the Swedish Social Democratic Party in 1970. Viewed as an environment that would create ‘good democratic citizens’ and an open society, this attempt at integrating different social and ethnic groups was ultimately a failure. These newly built suburban neighbourhoods were meant to symbolise the ‘pinnacle of Swedish modernity’, but soon came to represent the shortcomings of modern social engineering (Schierup et al, 2014). Today, Fittja is home to some 7,500 people, more than half of whom are of non-Swedish origin. It is stigmatised as one of the poorest and most socially segregated of Stockholm’s satellite cities. The Million Programme estates are some of the most impoverished corners of Scandinavia with unemployment soaring to nearly 50 per cent. As Shabazz (2015) analysed in the public housing projects of Chicago, architecture was also a contributing factor to their downfall. High-rise housing structures, which pack large numbers of people in less space, enable racial segregation by effectively confining the marginalised group in certain parts of the city and cutting them off from the resources that would enable social and economic growth.

In its 2017 report, the Swedish Police Authority placed the Alby/Fittja district in the most severe category of urban areas with high crime rates. In a study from 2013, researchers at Stockholm University showed that the main difference in terms of criminal activity between immigrants and others in the population in Sweden was due to differences in the socioeconomic conditions in which they grew up. This means factors such as parents’ incomes and the social conditions in the area in which they grew up. According to Brå, the factors that lead to segregation also contribute to a higher level of crime amongst people with foreign backgrounds. Due to their reputation, an infamous term began to be used to describe areas like Fittja - the ‘No-Go Zones’. The Swedish Police Authority instead identifies them as vulnerable areas which are sometimes ‘mistakenly’ called no-go zones. In a 2018 news article by Gareth Browne, titled “Police on the beat in Sweden’s so called no go zones”, the interviewed policeman is fearless about policing Fittja despite its status as a crime-stricken ghetto. “They call it no-go-zones, we call it go-go zones”, says the Officer. He mentions the poverty-trapped citizens being the ones often involved in crimes and not the immigrants who are instead busy trying to make a better life for themselves.

In 2015, at the height of Europe’s migration crisis, Sweden took in 163,000 asylum seekers. Three years on, the populist, anti-immigration Swedish Democrats were swelling in the polls, vowing to cut immigration to an absolute minimum and deport any foreign-born person convicted of a crime. The everyday citizen’s perception of immigrants linked to increased crime rates may be a result of politicians cherry-picking statistics to support their agenda, downplaying the effect of socio-economic factors and highlighting migration factors alone as a cause for increased criminal activity. As Fainstein (2014) states, theorists in the deliberative democracy paradigm claim that people’s views are informed by interaction with others, not their self-interests (Fischer & Forester, 1993).

In a CBSN interview from 2019, the chief superintendent of Botkyrka Municipality, who has been working in vulnerable zones for 18 years, strongly rejects the existence of no-go zones in Stockholm but rather it being a social construct. As he says, there is an insecurity amongst people who believe the new migrants come in and use Swedish tax pay to support their living costs. The rising alternative media sites that have emerged in the recent years also play a role by publishing a disproportionate number of stories that focus on crime committed specifically by immigrants. Media coverage, backed by political agenda, is more than oftentimes successful in influencing people to think in a certain direction. The dominant and stereotypical image of a peripheral area with concentrated social-housing estates, as theorised by Dikeç (2016), is influenced by the fearful dystopian images of American Ghettos and urban unrest occurring in other countries which are broadcast in media internationally. While it may be assuring to hear law enforcers dismiss the existence of the term ‘no-go zones’ as a mere social construct, it is also a reflection of the general attitude of authorities and lack of importance given to combat the internalised segregation in Swedish society. Moreover, the Swedish sustainability model has a tendency to avoid conflicts and downplay trade-offs. There needs to be a change in this attitude. The ultimate intent that Susan Fainstein represents through her work, is to make the implicit explicit.

Master Plans tend to hide their market-driven development goals behind the facade of achieving a “sustainable society”. In analysing the City Plan 2040 and the RUFS 2050 it is clear how power relations (as determined by the interaction between state authority, economic ownership, and urban residents) affect urban outcomes and how spatial relations reinforce injustice. This is the crucial issue for study, as Manuel Castells’s La Question Urbaine (1972, 1977) and David Harvey’s Social Justice and the City (1973) discuss. State authorities and larger stakeholders tend to prioritise development that favours the city, and ultimately the country’s position in the global competitive landscape. It is not within the power of municipal governments to achieve transformational change. Only the nation state has this kind of leverage. At the same time, decisions made at the municipal level, involving housing, transport, and recreation, can make life better or worse. There needs to be a change in the rhetoric around urban policy from a focus on competitiveness to a discourse about justice that can improve the quality of life in multiethnic suburbs (Fainstein, 2014).

Although it may be difficult to achieve structural transformation, Holden’s (2004) polycentric city model, which suggests developing concentrated centres within the existing fabric of a city, may be a plausible solution. Theoretically this may require adaptive reuse, retrofitting or repurposing of buildings to convert central nodes into publicly accessible urban assets. “New ideas must use old buildings,” said Jane Jacobs in her seminal book The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Inserting new activities within an existing framework is increasingly becoming a defining aspect of contemporary architecture. From an urban perspective, adaptive reuse is a valuable strategy to create density and mitigate urban sprawl. With the introduction of new building functions, physical heterogeneity can become a point of social mixing. However, it is also important to acknowledge the tensions between heterogeneity and community which can be aggravated by diversity. According to Putnam (2007, p. 137), “immigration and ethnic diversity tend to reduce social solidarity and social capital. New evidence from the US suggests that in ethnically diverse neighbourhoods, residents of all races tend to ‘hunker down’. Trust (even of one’s own race) is lower, altruism and community cooperation rarer, friends fewer.” It is necessary to recognize differences and to understand that living among those like oneself provides existential security. As Young (2000) suggests, neighbourhood homogeneity may have a positive outcome when situated within a metropolitan context of porous borders and heterogeneous groups.

Sociologist Saskia Sassen explains in a 2013 AD Interview, her vision of a utopian future city which allows the making of many sub-economies, not the economy, when new people come to a city. On a larger systemic scale, the desirable format is multiple articulations of the territory, not one endless metropolitan zone. She further explains this through the example of Chinese planning, where they expanded urban territories by building nine small cities around Shanghai rather than letting Shanghai become an endless metropolitan stretch. In her book, The Just City, Susan Fainstein suggests prioritising economic development programmes to the interests of employees and small businesses. Combining Holden’s polycentric city and Sassen’s territorial articulation, there may exist a solution in repurposing central nodes into institutional, business or ICT hubs. Studies show that for every new technology job, another two or three non-technology-based jobs are created in the same region. The new jobs that are being created range from the highly skilled to the unskilled. Job opportunities for unskilled or lesser skilled employees are important to improve the socio-economic conditions of migrants. As the OECD highlights, it is challenging to help newly arrived people to integrate into work and community life due to their lower level of education and skills.

The economic situation of migrant groups also gives them their “weaker status” in the housing market, which is already facing a shortage, and thus, access to limited housing choices. Mimi Hoang, in her presentation at reSITE 2016 presents Carmel Place, a residential building in Manhattan which New York City proposed as a pilot project to test out the effectiveness of micro-apartments in taming the city's unaffordable rental market. In the Stockholm context, collaboration between the municipality and architects in such experimental projects may provide a solution to their economic situation. For example, Fittja Terraces (Sjöterrassen), an urban regeneration project by Kjellander + Sjöberg Architects which mixes different sizes of households and forms of tenure, proved popular, with 80% of the property sold to local residents. However, Fainstein (2014) also argues that achieving economic equality wouldn’t necessarily reduce social inequality. Individuals would continue to express “their utterly inevitable passions of greed and envy, of domination and feeling of oppression, on the slight differences in social position that have remained ....” Recollections of persecution of one group by another or feelings of group superiority based on colour, nationality, or religion would still remain (Simmel, 1950). This is where the challenge reinserts itself at the human scale. After redefining planning policies and building the ideal city, is there a guarantee that it will overcome internalised segregation among different groups of people and their perceptions, which may be driven by a subjective sense of justice?

References

Andersson, H.O. & Bedoire, F. (1988). Stockholm: Architecture and Townscape. Prisma.

ArchDaily (2015). Fittja Terraces / Kjellander + Sjöberg Architects.

https://www.archdaily.com/594726/fittja-terraces-kjellander-sjoberg-architects

https://www.archdaily.com/594726/fittja-terraces-kjellander-sjoberg-architects

Browne, G. (2018). Police on the beat in Sweden’s so called ‘no go zones’. The National News: Europe.

https://www.thenationalnews.com/world/europe/police-on-the-beat-in-sweden-s-so-called-no-go-zones-1.767444

https://www.thenationalnews.com/world/europe/police-on-the-beat-in-sweden-s-so-called-no-go-zones-1.767444

Castells, M. (1972). La question urbaine. Paris: F. Maspero.

Cutieru, A. (2021). Adaptive Reuse as a Strategy for Sustainable Urban Development and Regeneration. ArchDaily.

https://www.archdaily.com/970632/adaptive-reuse-as-a-strategy-for-sustainable-urban-development-and-regeneration

https://www.archdaily.com/970632/adaptive-reuse-as-a-strategy-for-sustainable-urban-development-and-regeneration

Dikeç, M. (2016). Rage and Fire in the French Banlieues. Urban Uprisings: Challenging Neoliberal Urbanism in Europe. London: Maximillian Publishers, 95-119

Hällsten, M., Szulkin, R., Sarnecki, J. (2013). Crime as a Price of Inequality? The Gap in Registered Crime between Childhood Immigrants, Children of Immigrants and Children of Native Swedes. The British Journal of Criminology, 53(3), 456–481.

Holden, E. (2004). Ecological footprints and sustainable urban form. Journal of Housing and the Built Environment, (19), 91–109.

Fainstein, S. S. (2010). The Just City. Cornell University Press.

Fainstein, S. S. (2014). The Just City. International Journal of Urban Sciences, 18(1), 1-18.

Forester, J. (1993). Critical theory, public policy, and planning practice. Albany, NY: State University of NewYork Press.

Hamilton, A. R. & Foote, K. (2018). Police Torture in Chicago: Theorizing Violence and Social Justice in a Racialized City. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 108(2), 399–410. Taylor & Francis, LLC.

Harvey, D. (1973). Social justice and the city. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Jacobs, J. (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Random House, New York.

OECD. (2016). Working Together: Skills and Labour Market Integration of Immigrants and their Children in Sweden. OECD Publishing, Paris.

Putnam, R. D. (2007). E pluribus unum: Diversity and community in the twenty-first century. Scandinavian Political Studies, 30(2), 137–174.

Quintal, B. (2013). AD Interviews: Saskia Sassen. ArchDaily.

https://www.archdaily.com/418484/ad-interviews-saskia-sassen

https://www.archdaily.com/418484/ad-interviews-saskia-sassen

Sayer, A., & Storper, M. (1997). Ethics unbound: For a normative turn in social theory. Environment and planning D: Society and space, 15(1), 1–18.

Schierup, C., Ålund, A., Kings, L. (2014). Reading the Stockholm riots – a moment for social justice?. Race & Class 55(3), 1 –21.

Shabazz, R. (2015). Spatializing blackness: Architectures of confinement and black masculinity in Chicago. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Simmel, G. (1950). The sociology of Georg Simmel. (Trans. and edited by K. H. Wolff). NewYork, NY: Free Press.

Soja, E. W. (2010). Seeking spatial justice. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Stott, R. (2016). How Migration Will Define the Future of Urbanism and Architecture. ArchDaily.

https://www.archdaily.com/790818/how-migration-will-define-the-future-of-urbanism-and-architecture

https://www.archdaily.com/790818/how-migration-will-define-the-future-of-urbanism-and-architecture

Stott, R. (2016). Saskia Sassen, Krister Lindstedt and Mimi Hoang on the Architecture of Migration. ArchDaily.

https://www.archdaily.com/792826/saskia-sassen-krister-lindstedt-and-mimi-hoang-on-the-architecture-of-migration

https://www.archdaily.com/792826/saskia-sassen-krister-lindstedt-and-mimi-hoang-on-the-architecture-of-migration

Sweden. Ministry for Foreign Affairs. (2017). Facts about migration, integration and crime in Sweden.

https://www.government.se/articles/2017/02/facts-about-migration-and-crime-in-sweden/

https://www.government.se/articles/2017/02/facts-about-migration-and-crime-in-sweden/

Sweden. Region Stockholm. (2018). RUFS 2050: Regional Development Plan for the Stockholm Region.

Sweden. Stockholms stad. (2018). Översiktsplan: Stockholm City Plan.

Sweden. Trygghets Kommissionen. (2020). Brottsstatistik Hotspot Karta 2020.

Young, I. M. (2000). Inclusion and democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.