"Machine landscapes sit at the center of where we are, they structure our entire modern existence, they deliver things that we want to our door, they connect us to each other, they become the vaults where our digital selves live, but in terms of architectural space they’re totally new because it’s a space without people, it’s architecture without occupants, it’s a strange new phenomenon. But whether we like it or not, this is the typology that will define our time."

-Liam Young, Speculative Architect

INTRODUCTION

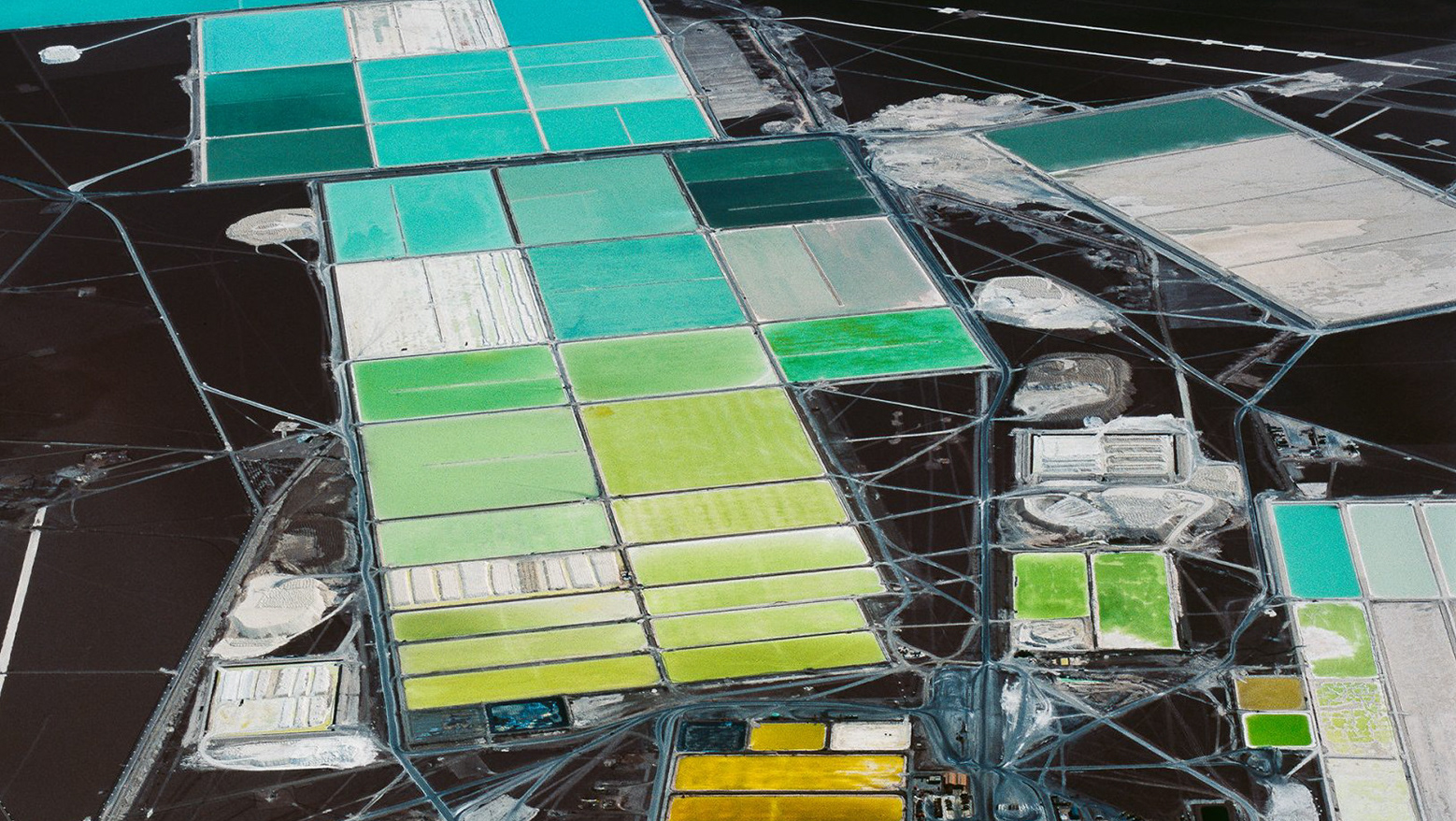

Planning for sustainable cities is a challenge in itself because the term “sustainability” is never static. Its definition changes at a pace that is increasingly difficult for planners to keep up with. Hence, the practice of sustainable design includes looking into the future and predicting what needs to be done. In our current age of automation, technology and machines, buildings are taking on a new typology that does not comply with patterns of human habitation. These machine landscapes set in ‘post-anthropocentric’ dystopian scenes are often seen in science-fiction films, contemporary artwork as well as photography, asserting its stronghold. It is therefore in our interest to discuss this typology that Hollywood and the media has been forecasting, if we want to speculate what our future cities might look like. And more importantly, how human beings would live in a world that operates beyond our scale, no longer dependent on human control. Humans have collectively established themselves as a species dependent on machines, something that began with the Industrial Revolution and is likely to remain in the foreseeable future. As a result of our needs, we have built mechanistic structures and kept them away in satellite landscapes that stand like solitary giants in our urban peripheries. Acknowledging the emergence of this new typology is the first step to innovate new ways of co-existing with these machines that sustain us.

This reflective essay explores the shifts we need to make on theoretical and design levels in order to initiate an epoch where both anthropocentric and post-anthropocentric infrastructure can exist. And among them, where humans and machines can prototype new relationships. My project ‘Södertälje EcoLab’ (from the Master Programme in Sustainable Urban Planning and Design, KTH) is weighed against the studied literature by Maciej Stasiowski (1) and John Peponis (2) to test if the proposed urban typology can be an antidote or an answer to the dominant narrative of a dystopian post-anthropocene world, i.e., a pedagogical and optimal alternative. To prescribe the said antidote and fill the unanswered gaps from the design project, I attempt to analyze the TV series Westworld (2016), set in a dystopian future, through Stasiowski’s lens (3). The intention behind selecting this particular show is that unlike Stasiowski’s examples, it allows us to see two different iterations of the post-anthropocene, one bleak, and another hopeful. To that end, I aim to discuss the following questions in this essay.

1. Is there an urban and architectural typology that allows humans to productively engage with our machine counterparts?

2. Can pedagogical design help change perspectives and see machine landscapes in a positive light?

Södertälje Symbiosis

The design project I undertook for the Textures Studio course, titled, ‘Södertälje EcoLab: Industry, Innovation, Ecology’, was primarily driven by the findings of the paper ‘Exploring Space, Exploiting Opportunities’ by Schiller et al (4). The literature argues for the use of geographical and spatial-material network analyses to successfully facilitate Industrial Symbiosis (IS). One of the questions raised in this paper, What spatially defined intervention(s) might support IS facilitation? (5), was then explored in the project. The key principle of IS is that the output of one industry’s process becomes an input to another’s, turning waste into a resource (6). The companies that collaborate in an IS may be from different sectors but their proximity and colocation in the same geographical area allows the physical exchange of resources like fuel, energy, waste, and water. Although land prices are increasing and areas for expansion are limited, strategic spatial interventions can integrate new and old companies into the Symbiosis, while making space for housing or commercial developments. In Södertälje, symbiosis is already taking place between the Port, the Igelstaverket Heat & Energy Plant, Lantmännen, an agriculture cooperative, and ODEC Tankstorage, an oil and natural gas company. However, these synergies are part of the current global economy which still follows a linear model, i.e., raw materials are mined, processed into products, consumed and thereafter become waste. Consequently, global consumption of materials such as biomass, fossil fuels, metals and minerals, is expected to double in the next forty years, while annual waste generation is projected to increase by 70% by 2050 (7). Industrial Symbiosis is thereby part of the circular economic perspective, an alternative to the conventional take-make-waste model. For instance, being powered by renewable energy, decoupling economic growth from virgin resource extraction, keeping the limited resources in closed circulation, and minimizing generation of waste (8).

Based on these analyses, the following part of the project took off on the assumption that a successful Symbiosis will be established among the existing and new industries in Södertälje in 2050. A scenario was speculated where the industries collaborate with the municipality to shift a certain percentage of their global operations into undertaking urban development projects instead. This would mean that these industries cooperate with each other, share resources and take up responsibility for implementing the master plan; directly benefiting the citizens and their urban life. The project site includes Södertälje Port, the existing industrial landscape around it, the Canal and its banks. It has low density and multiple underused facilities at present which can be reprogrammed, densified and diversified. The Södertälje EcoLab proposal offers a viable alternative for a harbor front neighborhood, challenging the perception of living alongside industries, which would be transformed from austere to a nuanced and appealing lifestyle. As the name suggests, this project can be seen as an experimental living laboratory where human activities and industrial processes occur simultaneously. It is a collective symbiosis between sustainable living practices, industrial businesses, tech innovations and a thriving ecosystem.

Computational Landscapes

In a city like Södertälje, whose economy is highly dependent on the major companies located there, like Scania, AstraZeneca and Lantmännen, there is no option to remove them or slow down their expansion. At the same time more area is needed for densification and housing development. As Per Fredman, the VP of Sales & Marketing at Södertälje Port envisions, the solution to this would be inverse expansion (9), i.e., to create more space in the same area instead of sprawling out further. In other words, expand inwards by repurposing all the obsolete spaces into housing, public spaces, workspaces or green areas. An equation that works for both the industries and the people while mitigating ecological harm. To formulate a planning strategy that would fit the equation of ‘inverse expansion’, I explore the architectural capabilities of using a modular design element like the ‘Truchet’ tiling concept. First described in a 1704 memoir by Sebastien Truchet (10) and popularized in 1987 by Cyril Stanley Smith (11), the Truchet pattern has an algorithmic logic behind it. The master plan was thus generated computationally with different parameters and constraints like the site area, boundaries, extent, axial lines, variability, radius, and scale. Figure 2 shows the final result of contiguous water and land clusters.

Figure 2. Master Plan for the Project “Södertälje EcoLab” projected at the year 2050

"They constantly process our waste, accept our trash, and distribute our electricity. They are our prostheses. They keep us alive and able, for a minute, to forget the precariousness of our existence here and of our total biological dependence on a series of machines, wires, and tubes, humming loudly in some far off place."

Jenny Odell, Satellite Landscapes

The first reason behind following this form-finding process is because it allowed for the creation of repeating patterns where each piece is a combination of the basic convex and concave elements (12). Within the Symbiosis this meant that Truchet modules prefabricated by local construction companies would be shipped to the site, unloaded with cranes and assembled in place with Scania’s equipment (Figure 3). However, restructuring and terraforming the existing land to create the EcoLab would generate mass construction waste. This will then be managed by Telge Återvinning AB, which in 2050 is envisioned to become a larger company for innovative waste disposal and recycling methods. Most of these construction wastes would also be reused in building workplaces for the new industries that will join the Symbiosis. The second reason is that in Truchet tiling, adjacent tiles can create much larger contiguous edge connecting patterns (13). This means that it would increase the surface area between land and water and more people living in the Eco Lab would have access to a waterfront edge. The third reason is, it allows planning in such a way that the industrial and residential blocks are in clear sight of each other but physically separated. This is preferable so as to keep people away from safety hazards.

Predominantly, there is a pedagogical function underlying all the aforementioned reasons. By living in the EcoLab, where the wetlands are a part of the water treatment system, where the bathhouses are powered by excess heat from the industries, where container vessels carry fuel through the Canal; individuals will be witnessing these processes in real time, everyday, through their daily activities. The labyrinth-like plan increases the opportunity for every individual to observe these mechanistic functions at least once a day, while heading to work or school or home. This ought to educate the passers-by about the industrial processes sustaining our daily activities. That we are biologically dependent on the machines we keep out of our sight. This would foreseeably trigger them to contemplate on our destructive production and consumption patterns.

Figure 3. Synergies in the Industrial Symbiosis that directly benefit the users and the ecosystem

Pedagogical Functions

Despite the pedagogical intent behind the planning strategy, the resulting spatial network may or may not be effective in implementing and realizing that quality. The project is thus analyzed from another angle with respect to John Peponis’s theory (14) of how the city acts as a pedagogic tool for individual and collective learning among its citizens, leading to intellectual and emotional development. A city can support the process of discovery and learning only if it induces exploratory navigation or open search, for which it needs to be rich, diverse, dense, well-connected and intelligible (15). Richness and diversity comes from the variety of behavioral settings and stimuli that a city offers. Assuming the presence of substantial mixed-use (16) programs inside the buildings, EcoLab offers urban diversity through its parks, bridges, docks, harbors, bathhouses, beach parks, wetlands, ponds, and promenades. Density in terms of the amount of people that can inhabit this neighborhood as compared to its previous condition is evidently much higher.

"…the way in which the spatial structure of the city as a physical artefact opens up an affective, cognitive and social space of exploration which interacts with the formation of self …" (17)

However, coming to the aspect of intelligibility, the city requires a network of major streets and different subsets of secondary streets; the connection between which forms the cognitive skeleton of the city. Without this quality the streets would become intimidating and unwelcoming to a resident. To that effect, the masterplan of EcoLab has been critiqued on the absence of intelligibility - how would an individual navigate through its maze-like spatial network? In the current proposal, all streets are of approximately the same width and lack a central street that would act as an axis, a reference for navigation plans and cognitive maps. To ensure the effectiveness of its pedagogical functions, the pedestrian street network needs to be redesigned, keeping in mind hierarchy and intelligibility.

On the other hand, unpredictability can also allow open search. Destinations are as likely to be discovered along the way, as they are to be found at the end of a journey. (18) Discovering new paths and places upon chance, gathering new knowledge of what is available, and identifying new corners of the city, equally support the process of learning from one’s environment. Mazes or labyrinths are known to be characteristically unpredictable, which is why they are often used in psychology experiments to study spatial navigation and learning capacity. They can also be seen as an archetypal symbol of what Carl Jung called the individuation process (19), which aligns with Peponis’s theory. Although the maze-like typology might be challenging to navigate compared to an ideal street network, it fits into the agenda of exploring new ways of living, nurturing collective learning and promoting ecologically conscious social activities. This would also forge a local identity of human-machine co-existence and a culture of responsible production and consumption in the EcoLab, and eventually the rest of Sodertalje.

Post-Anthropocentric Typologies

By redesigning an intelligible spatial network, the EcoLab will move closer to being an ideal solution for a sustainable Södertälje. However, that alone cannot alter the perspectives that people largely adopt and encourage them to readily accept these new human-machine living conditions. This calls for further scrutiny from an alternate theoretical perspective, i.e., Maciej Stasiowski’s article, titled, “No Figures in the Landscape. The Post-Anthropocentric Typologies of Architectural Settings in Science-Fiction Films”.(20) Reinterpreting the project through Stasiowski’s narrative reveals qualities that can be likened to what he calls ‘post-anthropocentric typologies’. The first reason for choosing the Truchet pattern for the masterplan is to allow modular, automated construction. By definition it is a computational, machine-made landscape with literal machines embedded in it. According to Stasiowski, automated constructions create settings which are incompatible with patterns of human habitation. The spatial network of EcoLab would certainly affect the pedestrian’s patterns of movement and everyday activities. Intelligibility was compromised in the process of facilitating industrial symbiosis and creating a neighborhood for both humans and machines. This supports the theory that humans have no place among mechanistic infrastructure because they cannot navigate through it. Moreover, this typology cannot be defined as any of the more widely known urban blocks that are used in planning strategies today, which indicates it could possibly be classified as a post-anthropocentric typology. If the project site had no constraints and was allowed to expand beyond the railway tracks, seeping into mainland Södertälje, it would look no less than what Stasiowski terms an “agglomeration of cells in an ever-growing urban sprawl”. (21) Hence, there are a few inconsistencies between the project’s intended outcome and actual result.

In his article, Stasiowski looks towards science fiction films to study the iconography of buildings designed to operate outside humans, citing scenes from Blade Runner 2049 (dir. Denis Villeneuve, 2017), Captive State (dir. Rupert Wyatt, 2019), Transcendence (dir. Wally Pfister, 2014), and more. On the other hand, he also discusses the works of artist Jenny Odell, photographer Edward Burtynsky, author Philip K. Dick and architect Liam Young, to uncover these structures we are already building in our anthropocene reality. Jenny Odell’s work titled “Satellite Landscapes'' is based on unresolved questions about the individual’s relationship to infrastructural systems. Odell uses satellite imagery to capture places whose existence feels peripheral to immediate experience, geographically, psychologically or both. These “Satellite Landscapes” sustain our modern lifestyle that we take for granted: factories, container ships, substations, data centers, cables, pipelines, power plants, wastewater treatment plants, dumps, landfills, and so on. (22) By observing satellite imagery of the Sodertalje Hamn area today, one can see how human settlements trail off right at the emergence of the industrial area. The only co-existence here occurs where some of the older industrial buildings have been reprogrammed into commercial spaces. This genre of work is important as it provides a rare window to observe our exhaustive impact on the planet and witness the industrial endeavors taking place parallelly with the dumping grounds created from its waste. (23) Both Stasiowski and Odell describe these post-anthropocentric structures as entities that incite a feeling of confusion, terror and paralysis. Something that needs to be repressed and kept far away from human sight. Something unpleasant, uncomfortable and impossible to consider cohabiting with. And yet, as Odell reiterates, the reason why these structures are unsettling, might be because they are deeply, fully human and at the same time unrecognizably technological. The question is, how can we collectively change this mindset to instead perceive them as extensions to the human body and develop a new vocabulary around them?

Science-Fiction Narratives

Westworld by Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy, based on the 1973 film of the same name (dir. Michael Crichton) is a critically acclaimed TV Series, set in a dystopian, neo-western reality that explores complex questions dealing with humanity, consciousness, reality and free will by taking its characters as well as the audience through an intellectual maze. The set-design and architectural choices have garnered international attention from the design community. What makes Westworld relevant to this discussion is because unlike most science-fiction films, it depicts two different narratives of the post-anthropocene simultaneously - dystopian and utopian.

Themed after the titular old-American wild west, "Westworld" is an immersive no-limits amusement park catering to rich guests who go there to escape their orderly lives and exercise their primal nature in a world without consequences. The location of the Park in context of the real world has not been unveiled, but it is known to be at least the size of a small country. Delos Inc, its owner and operator, has terraformed multiple parks of this scale with different themes. As the plot progresses, the Park is revealed to be a giant hidden maze meant for sentient humanoid robots to solve and become conscious and for the human guests to rediscover their humanity and purpose. In my interpretation, this is how Westworld uses iconographies such as the labyrinth as a pedagogical tool to appeal to its viewers’ conscience and provoke contemplation.

Embedded inside a large mesa, the corporate headquarters of Delos Inc extend deep underground; a scaleless, self-contained, operations and hospitality complex for the Park, containing everything from office spaces to living quarters, manufacturing facilities, and the control room. As seen in Figure 4, ‘underground’ is a relative term in this case, since a mesa exists at a height above its surrounding plains. Each level inside the building appears the same, glossy white surfaces, stone black floors, glass partitions, and blinding fluorescent lights, with the occasional red lighting to signify authority or flickering blue lights to signify obsolete workspaces. All production work is done by advanced machinery and robot arms, leaving only the intellectual work and security handling to the human staff. A reality that is operated and populated by humans on the surface but the real processes controlled by machines behind hidden layers. As Stasiowski points out, these typologies have no need for following the Vitruvian Man’s measurements, because they do not operate within the realm of humans. Among these levels, there also exists the exclusion zones of autofac (24) areas; with system malfunctions where the lights don’t work, where the coolers are flooding, the old machinery is piled, and decommissioned robot bodies stand in rows like an army of corpses. A concealed but true wasteland, with implications digging deeper than a landfill. Westworld is an allegory of the dystopia created as a consequence of human dependence on machines. With these visuals, Westworld has successfully reinstated the terror of the post-anthropocene in its audience.

Figure 4. Section of the Corporate Headquarters located within the Theme Park. Found on Westworld's fanservice website (25)

"In the age of the network, however, the body is no longer the dominant measure of space; instead it is the machines that occupy the spaces that now define the parameters of the architecture that contains them – an architecture whose form and materiality is configured to anticipate the logics of machine perception and comfort rather than our own." (26)

Grounded Futurism

As the show progresses, an alternate iteration of the post-anthropocene is depicted in Westworld, i.e., ‘Grounded Futurism’ in the year 2058. This was intended by the production designer Howard Cummings (27) to imagine a future starkly different from the scenes in Blade Runner. One with less traffic, less overcrowding, more greenery, more cleanliness and more order. The balance of old and new buildings make it welcoming and not alienating. Interestingly, this season was filmed in 2019, the same "future" year in which Blade Runner 1982 (dir. Ridley Scott) envisioned Los Angeles as a cyberpunk layered megalopolis with streets closely resembling today’s Bangkok, and jet-stream-level offices above it. The fact that Scott’s imagination, like many others’ did not nearly manifest in our present reality, is perhaps proof that dystopian future narratives are oftentimes merely born from the fantasies or fears of a handful filmmakers and storytellers.

The filming locations include present day Los Angeles and stand-out buildings from different cities to create the perfect anthropocene city. Architect Bjarke Ingels, who is an informal consultant on the show, suggested that the main inspiration should be Singapore with its impeccable modern architecture like the ParkRoyal Hotel by WOHA, Lasalle College of the Arts by RSP Architects, and the Helix Bridge by Philip Cox. Landmarks taken from other cities are La Fábrica in Barcelona by Ricardo Bofill, City of Arts and Sciences in Valencia by Santiago Calatrava; Wallace Cunningham’s Crescent House in California; Boeri’s Vertical Forest in Milan; and Frank Lloyd Wright’s Millard House in Pasadena. Westworld’s future world is different from all other future worlds for another reason. The show has a precise conception of urban space management and technology. Some examples being, all citizens have a headset and portable device for communication, there are no more traffic jams, electric taxis drive themselves, almost all traffic runs underground, passenger drones that are solar-powered, suspended walkways and electric motorcycles that park themselves in their charging stations. And the most optimistic vision - climate change is no longer an issue, thanks to giant carbon-eating machines. In conclusion to this fiction analysis, one proposition is that co-existing with machines need not be feared or prevented. The scale of human needs and its impact on the planet will continue to grow, hence, the scale of machines required to support this will inevitably grow along with it. It may prove to be an optimistic solution to tackle the recurring issues in our anthropocene reality.

Figure 5. Calatrava’s City of Arts & Sciences behind a flying passenger drone, as seen in Season 3 of Westworld

Alternate Iterations

Stasiowski mentions data centers, automated warehouses and similar “user-proof” structures as a typology that functions better without human control. However, such architecture designed to function with “no bodies in mind” might in fact help in limiting our harmful impact on the ecosystem. He advocates for the benefits of co-existing with the mechanistic architecture that we are already building. If we focus only on a pessimistic outcome, we might miss out on the possibility of designing ecologically-oriented, sustainable projects. There are numerous ways to productively engage with the machine world, which have not yet been fully harnessed. From this perspective, I substantiate the feasibility of projects like Södertälje EcoLab, which is centered around both the human and the habitat. As Stasiowski concludes in his article, a typology that is not an intrusion, but a site-specific remodeling of the landscape. (28)

Ecologically-oriented innovations are already taking place in Södertälje. Scania, for instance, is introducing autonomous transport solutions, self-driving trucks, (29) and collaborating with ABB Robotics to develop robotic arms for packaging and handling systems. Their intention is to automate all the tedious, repetitive and risky tasks to the machines and allow their human staff to focus on more creative, long-term responsibilities. Their Smart Factory Lab tests these new solutions before implementing them in production. While this reduces job positions in the production sector it also increases job openings in the other sectors that require human intelligence for creating things. (30) Thereby proving that humans won’t lose their relevance in the production line. Furthermore, students, interns and a young workforce are being hired by partnering with Stockholm University and KTH. Urban planners and designers can play a larger role in creating networks like these where opportunities for collaboration and education emerge from the applied technical solutions.

Snøhetta’s project titled “The Spark” (2018-) is worth mentioning as an ideal example of symbiosis, pedagogy, ecosystem and people-oriented design coming together in one project. It was conceived as a prototype model for a sustainable data center that works in symbiosis with power plants to produce energy from its excess heat, along with industries, housing and recreational spaces like pools, spas, gyms, etc. The project aims to transform the “high-energy-consuming typology” of a data center into an energy producing resource for communities to generate their own power. The first pilot study will be located in Lyseparken, Norway, where its feasibility will be tested on a real site. Instead of building it in a remote area, placing it in the heart of the city and designing it as a physical venue worth visiting, makes it symbolic of the “very body and mind of a living and breathing city”. Using iconographies in this way can also prove to be successful in changing people’s perception of living in the age of storage. Although such paradigms are more often ‘forecasted’ than actually implemented, as Stasiowski notes, it is still a viable solution that would allow cities to get more from less.

Conclusion

"Once the definition of a new territory has been outlined we need to come to some consensus of what to do next. Do we go to war, do we colonize or sneak our way in, or do we stand at the edges and watch on from afar?" (31)

Reviewing the Ecolab project against the literature brings forth a different perception of itself, both cynical and opportunistic. Regardless of the post-anthropocentric qualities it harbors, the labyrinth-like master plan demonstrates the possibilities and positive outcomes of living alongside industries, by facilitating symbiosis and by functioning as a pedagogical device.

The post-anthropocentric typologies seen in sci-fi films are not forecasts of a dystopian future where automation is threatening our existence. They are not cautionary tales born from the fear of becoming redundant on a machine-led planet. But rather, a call for changing perspectives and ideologies so that we can keep up with the pace of technology and not lose our importance as time passes. We have kept far away from the machines that sustain us and turned our gaze away from them, as a result of which these landscapes have emerged. As planners and urban designers, we cannot merely reclaim this lost territory by trying to sneak back in and parasitically occupy these landscapes. We have a larger responsibility to identify opportunities and create cities that will radically shift our current patterns of living and thinking. Thus challenging the very social logic behind production and consumption. Adopt a pedagogical approach that would stimulate people living in these cities, to rethink about the consequences of their destructive habits. The founding machines of the post-anthropocene are already here, critical and fundamental for humans, embedded in the urban fabric with a sense of presumed permanence. In these new landscapes, where our existence feels insignificant, the scale of our bodies feel immaterial and our occupations seem irrelevant, we have to confront these uncomfortable feelings and explore new ways to productively engage with our non-human cohabitants.

Footnotes

1. Stasiowski, “No Figures in the Landscape,” 24-45.

2. Peponis, “On the pedagogical functions of the city,” 219-251.

3. Analyze the show with a similar narrative style and description to Stasiowski’s article.

4. Schiller et al., “Exploring Space, Exploring Opportunities,” 792.

5. Schiller et al., “Exploring Space, Exploring Opportunities,” 796.

6. Chertow, “Uncovering Industrial Symbiosis,” 11-30.

7. European Commission, “Closing the loop – An EU action plan for the Circular Economy.”

8. (SDG 12 - Responsible Consumption & Production) Sönnichsen et al., “Systems make it possible, People make it happen.”

9. Södertälje Hamn, “A Port Preparing for Growth.”

10. Truchet, “Mémoire sur les combinaisons," 363-372.

11. Smith et al., “The tiling patterns of Sebastien Truchet and the topology of structural hierarchy," 373-385.

12. Krawczyk, “Infinitely Variable Tiling Patterns”.

13. Krawczyk, “Infinitely Variable Tiling Patterns”.

14. Peponis, “On the pedagogical functions of the city,” 219-25.

15. Peponis, “On the pedagogical functions of the city,” 246.

16. Unlike the fabricated “mixed-use developments” seen in contemporary sustainability projects.

17. Peponis, “On the pedagogical functions of the city,” 219.

18. Peponis, “On the pedagogical functions of the city,” 244.

19. Diamond, “Why Myths Still Matter.” The goal is to reach the center, the Self, the core of our being; and then find a way back out of the labyrinth, forever transformed by this experience. This inward and outward expedition is repeated over and over, each time yielding new riches.

20. Stasiowski, “No Figures in the Landscape,” 24-45.

21. Stasiowski, “No Figures in the Landscape,” 29.

22. Odell, “Satellite Landscapes.”

23. Baichwal, “Manufactured Landscapes.”

24. Acronyms for ‘automatic’ and ‘factory’, from Philip K. Dick’s 1958 short story, “Autofac”.

25. Delos Corporate Map, HBO Westworld, fanservice website http://www.delosincorporated.com/

26. Young, “Introduction, Neo-Machine: Architecture Without People,” 11.

27. Pelag, “For Westworld Season 3, Los Angeles of 2058 Was Built With Input From Bjarke Ingels.”

28. Stasiowski, “No Figures in the Landscape,” 41.

29. Scania, “Trials of Scania's self-driving trucks on public roads.”

30. Scania, “Scania’s Smart Factory Lab explores emerging technologies.”

31. Young, “Introduction, Neo-Machine: Architecture Without People,” 13.

2. Peponis, “On the pedagogical functions of the city,” 219-251.

3. Analyze the show with a similar narrative style and description to Stasiowski’s article.

4. Schiller et al., “Exploring Space, Exploring Opportunities,” 792.

5. Schiller et al., “Exploring Space, Exploring Opportunities,” 796.

6. Chertow, “Uncovering Industrial Symbiosis,” 11-30.

7. European Commission, “Closing the loop – An EU action plan for the Circular Economy.”

8. (SDG 12 - Responsible Consumption & Production) Sönnichsen et al., “Systems make it possible, People make it happen.”

9. Södertälje Hamn, “A Port Preparing for Growth.”

10. Truchet, “Mémoire sur les combinaisons," 363-372.

11. Smith et al., “The tiling patterns of Sebastien Truchet and the topology of structural hierarchy," 373-385.

12. Krawczyk, “Infinitely Variable Tiling Patterns”.

13. Krawczyk, “Infinitely Variable Tiling Patterns”.

14. Peponis, “On the pedagogical functions of the city,” 219-25.

15. Peponis, “On the pedagogical functions of the city,” 246.

16. Unlike the fabricated “mixed-use developments” seen in contemporary sustainability projects.

17. Peponis, “On the pedagogical functions of the city,” 219.

18. Peponis, “On the pedagogical functions of the city,” 244.

19. Diamond, “Why Myths Still Matter.” The goal is to reach the center, the Self, the core of our being; and then find a way back out of the labyrinth, forever transformed by this experience. This inward and outward expedition is repeated over and over, each time yielding new riches.

20. Stasiowski, “No Figures in the Landscape,” 24-45.

21. Stasiowski, “No Figures in the Landscape,” 29.

22. Odell, “Satellite Landscapes.”

23. Baichwal, “Manufactured Landscapes.”

24. Acronyms for ‘automatic’ and ‘factory’, from Philip K. Dick’s 1958 short story, “Autofac”.

25. Delos Corporate Map, HBO Westworld, fanservice website http://www.delosincorporated.com/

26. Young, “Introduction, Neo-Machine: Architecture Without People,” 11.

27. Pelag, “For Westworld Season 3, Los Angeles of 2058 Was Built With Input From Bjarke Ingels.”

28. Stasiowski, “No Figures in the Landscape,” 41.

29. Scania, “Trials of Scania's self-driving trucks on public roads.”

30. Scania, “Scania’s Smart Factory Lab explores emerging technologies.”

31. Young, “Introduction, Neo-Machine: Architecture Without People,” 13.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Browne, Cameron. “Truchet curves and surfaces.” Computers & Graphics 32, no. 2 (2008): 268-281.

Burtynsky, Edward. “China.” Accessed January 3, 2021.

https://www.edwardburtynsky.com/projects/photographs/china

https://www.edwardburtynsky.com/projects/photographs/china

Burtynsky, Edward. “Manufactured Landscapes: By Jennifer Baichwal.” Accessed January 3, 2021.

https://www.edwardburtynsky.com/projects/films/manufactured-landscapes

https://www.edwardburtynsky.com/projects/films/manufactured-landscapes

Chertow, Marian R. “Uncovering Industrial Symbiosis.” Journal of industrial Ecology 11, no. 1 (2007): 11-30.

Crook, Lizzie. "Why aren't architects designing the environments for video games? Asks Liam Young." Dezeen. Last modified October 30, 2019.

https://www.dezeen.com/2019/10/30/liam-young-dezeen-day/

https://www.dezeen.com/2019/10/30/liam-young-dezeen-day/

Diamond, Stephen A. “Why Myths Still Matter (Part Three): Therapy and the Labyrinth.” Psychology Today. Last modified November 26, 2009.

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/evil-deeds/200911/why-myths-still-matter-part-three-therapy-and-the-labyrinth

https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/evil-deeds/200911/why-myths-still-matter-part-three-therapy-and-the-labyrinth

European Commission. Closing the loop - An EU action plan for the Circular Economy. European Commission. Brussels, 2015. COM(2015) 614 final.

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:8a8ef5e8-99a0-11e5-b3b7-01aa75ed71a1.0012.02/DOC_1&format=PDF

https://eur-lex.europa.eu/resource.html?uri=cellar:8a8ef5e8-99a0-11e5-b3b7-01aa75ed71a1.0012.02/DOC_1&format=PDF

Kalundborg Industrial Symbiosis. “Explore The Kalundborg Symbiosis.” Accessed December 26, 2021.

http://www.symbiosis.dk/en/

http://www.symbiosis.dk/en/

Kalundborg Industrial Symbiosis. “Guide For Industrial Symbiosis Facilitators.” Accessed December 26, 2021.

http://www.symbiosis.dk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Guide-for-IS-facilitators_online2.pdf

http://www.symbiosis.dk/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/Guide-for-IS-facilitators_online2.pdf

Odell, Jenny. “Satellite Landscapes (Transportation Landscape, Waste Landscape, Manufacturing Landscape, and Power Landscape) 2013-2014.” Accessed December 29, 2014.

https://www.jennyodell.com/satellite-landscapes.html

https://www.jennyodell.com/satellite-landscapes.html

Pelag, Oren. “For Westworld Season 3, Los Angeles of 2058 Was Built With Input From Bjarke Ingels.” Architectural Digest. Accessed January 3, 2022.

https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/westworld-season-3-set-design-interveiw

https://www.architecturaldigest.com/story/westworld-season-3-set-design-interveiw

Peponis, John. “On the pedagogical functions of the city: a morphology of adolescence in Athens, 1967-73.” The Journal of Space Syntax 7, no.2 (2017): 219-251.

Scania. “Scania’s Smart Factory Lab Explores Emerging Technologies.” Last modified April 24, 2019.

https://www.scania.com/group/en/home/newsroom/news/2019/scanias-smart-factory-lab-explores-emerging-technologies.html

https://www.scania.com/group/en/home/newsroom/news/2019/scanias-smart-factory-lab-explores-emerging-technologies.html

Scania. “Trials of Scania's self-driving trucks on public roads.” Last modified June 14, 2017.

https://www.scania.com/group/en/home/newsroom/news/2017/trials-of-scanias-self-driving-trucks-on-public-roads.html

https://www.scania.com/group/en/home/newsroom/news/2017/trials-of-scanias-self-driving-trucks-on-public-roads.html

Schiller, Frank, Alexandra Penn, Angela Druckman, Lauren Basson, and Kate Royston. “Exploring Space, Exploring Opportunities. The Case for Analyzing Space in Industrial Ecology.” Journal of industrial Ecology 18, no.6 (2014): 792-98.

Smith, Cyril Stanley, and Pauline Boucher. "The tiling patterns of Sebastien Truchet and the topology of structural hierarchy." Leonardo 20, no. 4 (1987): 373-385.

Södertälje Hamn AB. “A Port Preparing for Growth.” Last modified April 6, 2018.

https://www.soeport.se/en/news/a-port-preparing-for-growth/

https://www.soeport.se/en/news/a-port-preparing-for-growth/

Sönnichsen, Sönnich Dahl and Jesper Clement. “Systems make it possible, people make it happen, 2018.” Kalundborg Symbiosis. Accessed December 20, 2021.

http://www.symbiosis.dk/en/systems-make-it-possible-people-make-it-happen/

http://www.symbiosis.dk/en/systems-make-it-possible-people-make-it-happen/

Stasiowski, Maciej. “No Figures in the Landscape. The Post-Anthropocentric Typologies of Architectural Settings in Science-Fiction Films.” Kwartalnik Filmowy no. 110 (2020): 24-45.

Truchet, Sébastien. "Mémoire sur les combinaisons." Mémoires de l’Académie royale des sciences 1704 (1704): 363-372.

Young, Liam. “Introduction. Neo-Machine: Architecture Without People.” Architectural Design 89, no.1 (2019): 6-13.

Young, Liam. “Territorial Robots. Jenny Odell: Satellite Landscapes.” Architectural Design 89, no. 1 (2019): 32-35.

Zolotoev, Timur. “Landscapes Of The Post-Anthropocene: Liam Young On Architecture Without People.” New Urban Conditions. Last modified March 29, 2019.

https://strelkamag.com/en/article/landscapes-of-the-post-anthropocene-liam-young-on-architecture-without-people

https://strelkamag.com/en/article/landscapes-of-the-post-anthropocene-liam-young-on-architecture-without-people